Mexico's Next Border Problem

Today's migrant tragedy may soon give way to a much trickier economic challenge for the country’s new president

Mexico gets a new president tomorrow and she faces the same challenges from crime, migration and poverty that her predecessors struggled to address. But Claudia Sheinbaum's trickiest problem may lie in navigating rising tensions between the United States and China that threaten the heart of her country's business model.

The reorganization of the global supply chains presents Mexico with a historic opportunity as companies scramble to establish low-cost production inside America’s tariff walls. But the promise may turn into a trap as it dawns on Washington’s policymakers that the rise in imports from Mexico coincides with a rise in Mexico’s imports from China. The migrant crisis that now generates so much human tragedy may expand into a damaging trade skirmish, too.

The immediate question swirling around this climate scientist turned mayor of Mexico City is just how much she may try to distance herself from her mentor and predecessor Andrés Manuel López Obrador. He concentrated power in the executive during his six-year term and drew on the military for law enforcement, although without much demonstrable success in reducing the country's staggering crime rate or defeating its drug cartels. The murder rate per capita is triple what it is in the United States.

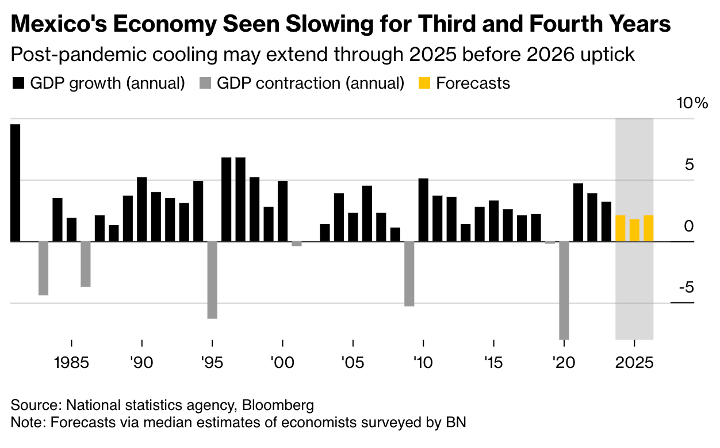

Transfer programs and a rising minimum wage have helped the poorest households and economic growth exceeded 3% for the last three years with a healthy boost from America's post-COVID rebound. But while AMLO, as he is known, kept a tight hand on budget spending for most of his term, he spent lavishly on pensions and infrastructure before the election leaving Sheinbaum with a likely deficit near 5% of GDP this year, the country's largest since the 1980s.

This has kept the Bank of Mexico especially cautious, announcing a second rate cut of just 25 bps last week to bring the benchmark rate to 10.50% with headline consumer price inflation at 4.7% for the first half of September. The peso is already one of the best-performing currencies against the dollar over the last two years, in spite of a recent selloff. This raises the costs of exports and reduces the value of remittances from overseas, leaving forecasters predicting growth may slow to 1.5% this year.

More problematic, however, has been AMLO's extensive judicial reform which he pushed through earlier this month and includes the election of judges. He insists it will reduce corruption, but critics fear it will do the opposite and scare off foreign investors. In rare public criticism, the U.S. ambassador suggested it would weaken North American economic integration while others worry it will complicate the scheduled review of the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement in 2026.

In an era of near-shoring and de-risking, this should be Mexico's golden moment as firms look for suppliers who are cheaper and safer from rising trade tensions between Washington and Beijing. Indeed, foreign direct investment has soared, hitting a record $31 billion in the first half of the year, including a $700 million Volvo truck plant in Monterrey. The largest investors by far come from the United States, followed by Europe and Japan. China isn't yet among the top 10, even if eye-catching headlines report mounting interest among its firms.

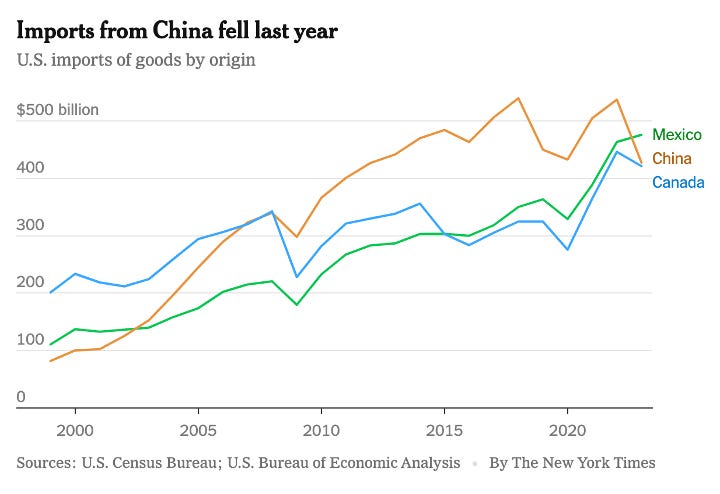

Rising investment naturally bolsters trade. Last year, Mexico returned to ranking as the leading source of U.S. imports for the first time in 20 years, displacing China. But look beneath the headline numbers. The U.S. represents some 80% of Mexico's exports and about 40% of its imports. Meanwhile, China accounts for barely 2% of its exports, but more than 20% of its imports (up from 16% a decade ago).

Chinese components that are “substantially transformed” in Mexico can be exported tariff-free to the U.S. But President Sheinbaum needs to brace for much more attention to these flows as America seeks to blunt the massive expansion of China’s manufactured exports. Chinese goods also avoid U.S. tariffs when they are incorporated into European, Japanese and Korean supply chains, but Mexican flows are already drawing the most attention.

Typically, former Donald Trump is leading the charge, threatening 100% tariffs on all cars coming from Mexico. He also falsely claimed that Chinese automakers are building plants in Mexico and promised 200% tariffs on notional production from these non-existent factories. These threats are problematic given the free trade deal, but they reflect mounting bipartisan consensus on China that threatens Mexico with collateral damage.

While Mexico cannot cut off Chinese imports, the new president may have to take her own tougher line on China’s subsidies and dumping practices. She will also need to convince American politicians that Mexican companies are truly engaged in “substantial transformation” rather than abetting tariff avoidance. If not, the current migrant crisis on her border will devolve into an economic calamity.