Next Year's Wars

The likeliest conflicts won’t move markets, but investors should watch for shifts in the background that will make the global order less predictable

“Peace on Earth” is this season’s perennial message, but the Council on Foreign Relations reminded us last week of just how distant the vision remains. In a world of streaming headlines and short attention spans, its Preventive Priorities Survey offers a welcome framing of the risks to U.S. interests posed by armed conflict next year. If you’re an investor, the list offers few surprises, but it leaves the unmistakable impression of deeper shifts at work.

First, a small word in defense of looking at wars through the lens of investors. All wars are tragedies that bring immense human suffering, economic loss and generational trauma. If arms dealers benefit from war, everyone else loses. But markets can serve as partial seismographs, not only measuring current geopolitical disruptions but also offering insight into the tectonic shifts beneath the surface.

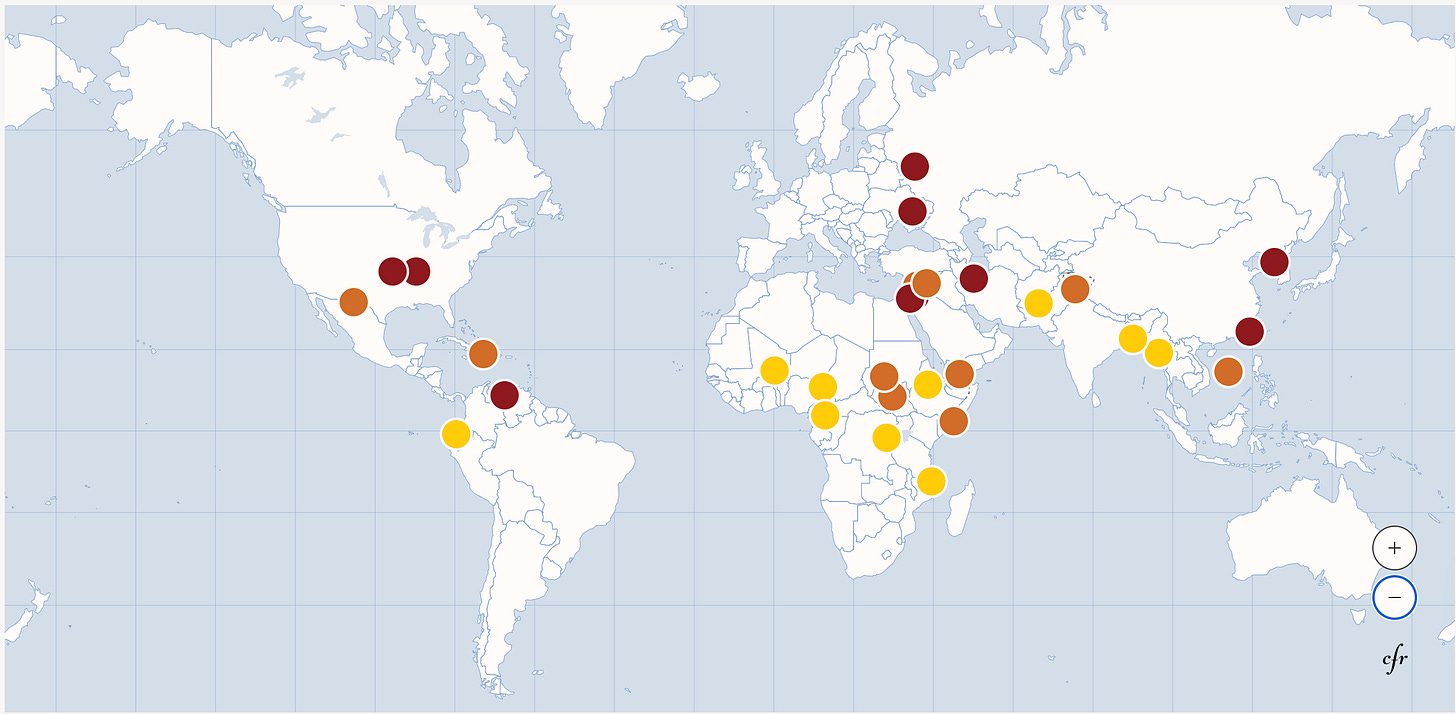

For the last 18 years, the Council has asked top U.S. policymakers and scholars to assess 30 active or possible conflicts. The usual suspects landed in the category deemed to be “high likelihood” and “high impact” for U.S. interests: Israel’s West Bank, Gaza Strip, Russia-Ukraine and Venezuela. “Political violence and popular unrest in the United States” may seem out of place in this section until it explains that the scenario is “exacerbated by heightened political antagonism and domestic security deployments.”

Amid soaring stock prices and rich valuations, this list should make investors cautious, especially given the potential for violence in some of the world’s largest oil-producing regions. But then you will recall this year that not even an attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities that triggered a reprisal against U.S. forces in the Gulf disrupted oil prices for more than a few hours. Oil prices matter, but supply diversification means global shocks are brief and rare.

Next on the list are conflicts tagged as moderately likely, albeit with significant impact. These include more missile exchanges between Iran and Israel, a cyberattack on U.S. critical infrastructure, a cross-strait crisis between China and Taiwan, armed confrontation between Russia and NATO and some outbreak of fighting with North Korea. Any one of these could trigger a stock market sell-off, but it’s hard to know how enduring the damage to the global economy would be.

Even a short confrontation over Taiwan could trigger global sanctions against China, but what are the odds that the world’s largest economies would even try to isolate China as they did Russia? Crippling U.S. infrastructure could mean significant economic disruption, but the market swoon would be brief if the Fed cut interest rates and Congress gave each American a $1,000 check.

Then there are the conflicts that have a lesser impact on U.S. interests, even if the human toll remains staggering. These include fighting in Haiti, Somalia, Yemen, Democratic Republic of Congo, Syria, Lebanon, Congo and elsewhere. Fighting in South Sudan has killed hundreds of thousands over the last decade, while the civil war in Sudan has killed almost as many over just the last few years.

Disruptions to rare-earth supplies are possible but unlikely to undermine the growth of any single country or industry. If these conflicts echo Vladimir Lenin’s theory about capitalist empires plundering the developing world for natural resources, most seem mainly fueled by ethnic differences and warlord rivalries.

What jumps out from the list, however, are the forces at work behind the headlines.

What would spook investors next year are the scenarios that fall under the category of “low likelihood, high impact.” These include U.S. military strikes on Mexican drug cartels and naval battles in the South China Sea that draw in China, the Philippines and the United States. Markets might also be shocked by events that the Council’s experts find difficult to imagine. A coup in Saudi Arabia? A terrorist attack on the Panama Canal?

What jumps out from the list, however, are the forces at work behind the headlines. President Donald Trump’s attempts to mediate some of these conflicts look laudable, but they are one-off efforts to strike deals that have delivered mixed results. At the same time, his administration has been undermining alliances and destroying institutions built up over decades to help prevent or resolve conflicts. The Trump administration, writes Paul Stares, who oversees the Council’s survey, has “systematically dismantled the very elements of the U.S. government dedicated to strategic foresight, conflict prevention, and peace-building without replacing them with anything better.”

The result has been a rising risk of unforeseen conflict as America’s priorities and commitments evolve unpredictably. Doubts about European security have grown now that Washington styles itself less as a defender against Russian aggression and more as a mediator of the conflict. Trump’s refusal to discuss what America would do in a war over Taiwan’s independence leaves Japan and South Korea feeling less secure. And the new “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine opens up fresh scenarios for conflicts across Latin America.

Assessing potential conflicts for their likely impact on U.S. interests helps frame the challenges for America’s diplomats next year. Few of these scenarios seem likely to have an immediate market impact, especially since the odds of disrupting key commodities supplies look low. But the shifting tensions beneath the surface create new risks that both diplomats and investors must track. If market shocks often bounce back fast, systemic change gets priced in slowly and durably.

Insightful framing of the CFR survey as a guide to systemic risk rather than just headline events. The observation that markets price individual conflicts quickly but systemic shifts slowly is spot on. Back when I was tracking portfolio reallocations during the 2022 energy crisis, the immediate shocks faded, but the underlying supply diversification plays persisted for months. The real anxiety here isnt any single flashpoint but the erosion of predictability itself, feels like tradingon shifting sand when institutional framewroks get gutted. Dealmaking without those backstops might calm tensions short-term but leaves everyone more exposed to tail risks nobody priced in.

What about Greenland and Svalbard? Will the US annex Greenland and Russia try to do the same with Svalbard?