When Does the Indispensable Nation Become Less Indispensable?

If negotiating U.S. trade deals becomes too hard, the rest of the world will move on.

As world markets convulsed last week, a simple reminder arrived from the head of one of the world’s oldest auction houses. “So far,” Oliver D. Stocker wrote the clients of Spink & Son, “barring any reciprocal tariff barriers by various trade partners, [the trade war] mainly affects collectors based in the USA.”

While most policymakers outside the White House and all investors everywhere fret over rising tensions, it’s worth remembering that this is still mainly a crisis made in America. And if U.S. officials don’t restore predictable trading relationships soon, Americans themselves will bear the greatest burden.

That’s not to minimize the lost savings from the stock market’s collapse, the rising recession risks from policy uncertainty, or the likely job losses from the sudden decoupling of U.S.-China trade. But it’s important to remember that the United States represents a quarter of the world’s GDP. Americans are the world’s richest consumers with the greatest appetites for inexpensive stuff, but for three-quarters of the world’s economy, life goes on.

If you are a numismatist client of Spink & Son, which dates its own business back to 1666, there’s very little you haven’t seen in the history of global commerce. But it’s probably still unusual to see tariffs on money itself, as Stocker offers his understanding of the rules coming into view for his clients:

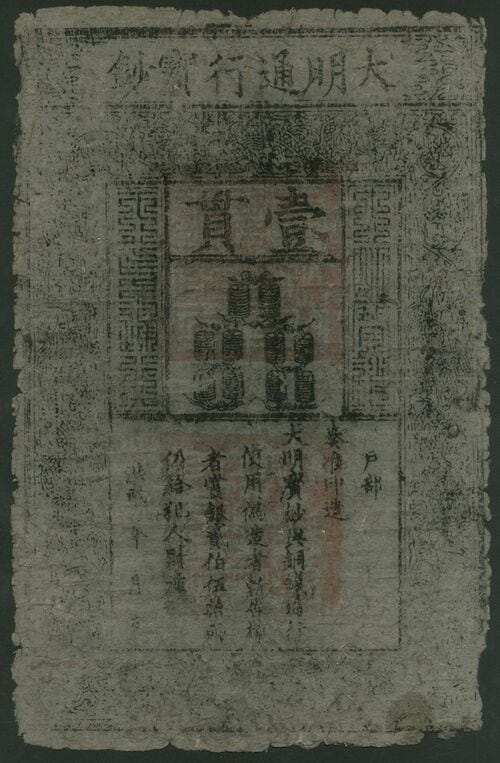

“[T]he tariff that will apply to the country of manufacturing where the collectable was struck or printed. So, a coin struck 2,000 years ago in ancient Greece, will be deemed as manufactured in Greece, and hence the 20% EU tariff will apply. An Indian banknote printed by De la Rue, or Bradbury Wilkinson in the UK 100 years ago, will be deemed manufactured in the UK, and a 10% rule will apply. And a Ming banknote printed in the 14th century in China (I love them!), will face a 104% tariff when arriving on US soil.”

This was written before President Trump announced a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs and ratcheted up China tariffs to 145%, but you get the idea. Whatever deals the Trump administration manages to negotiate over the next three months, average U.S. tariffs will rise well above the 2.5% average before it took office.

But, with a wink and a nudge, Stocker offers his collectors this:

“As most of you know, we offer some storage facilities in our London vaults and are happy to discuss storage of your purchases in London or Hong Kong, provided it does not contravene any international law.”

There, through the lens of ancient coins and other collectibles, is the future of world trade. Everything produced by 75% of the global economy will be more expensive for Americans -- unless it can be stored somewhere abroad until the tariff fever passes. Everything that other countries buy from each other will cost the same.

Matteo Cominetta, the shrewd head of macroeconomic research at Barings, points out that a universal tariff wall leaves American buyers no way to substitute purchases from a “bad” trading partner with orders from a “good” trading partner. Meanwhile, as retaliatory tariffs match wherever the U.S. imposes, other countries will find themselves trading with one another on much more favorable terms.

These patterns won’t all shift easily or quickly. As readers of our more frequent Substack publication already know (and sign up here if you’re not already one of them), a little rough math can help identify those who may try harder to strike a deal with Trump’s negotiators.

Meanwhile, as retaliatory tariffs match wherever the U.S. imposes, other countries will find themselves trading with one another on much more favorable terms.

Canadian and Mexican exports to the United States represent 24% and 31% of their economies, respectively. But China’s U.S. exports are just 3% of its GDP. That’s still a big number if you’re a Chinese leader already struggling to bolster growth. But it’s not big enough to change the way you have organized your economy or make big concessions to someone who has called your people cheaters and thieves.

It’s interesting that countries that seem most eager to strike a deal include Vietnam, for which U.S. exports are 22% of GDP, and Switzerland (16%), while Japan (3%) or Korea (5%) may be motivated to protect security relationships.

But the longer it takes to understand what deals Trump himself will accept, the easier it will be for other countries to look elsewhere. After that, trading partners must still cope with sectoral tariffs on steel and autos, with the possibility of more on pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. And who knows what trade policy will look like under the next U.S. president, even if it’s a Democrat?

“Everything will be okay in the end, and if it is not yet okay, it is not the end,” Stocker reassures his clients. Even if Americans emerge from this okay, it’s hard to see how they emerge better off.