The Runaway Train

Can anyone rein in China's trade surplus?

It is a massive number by any measure.

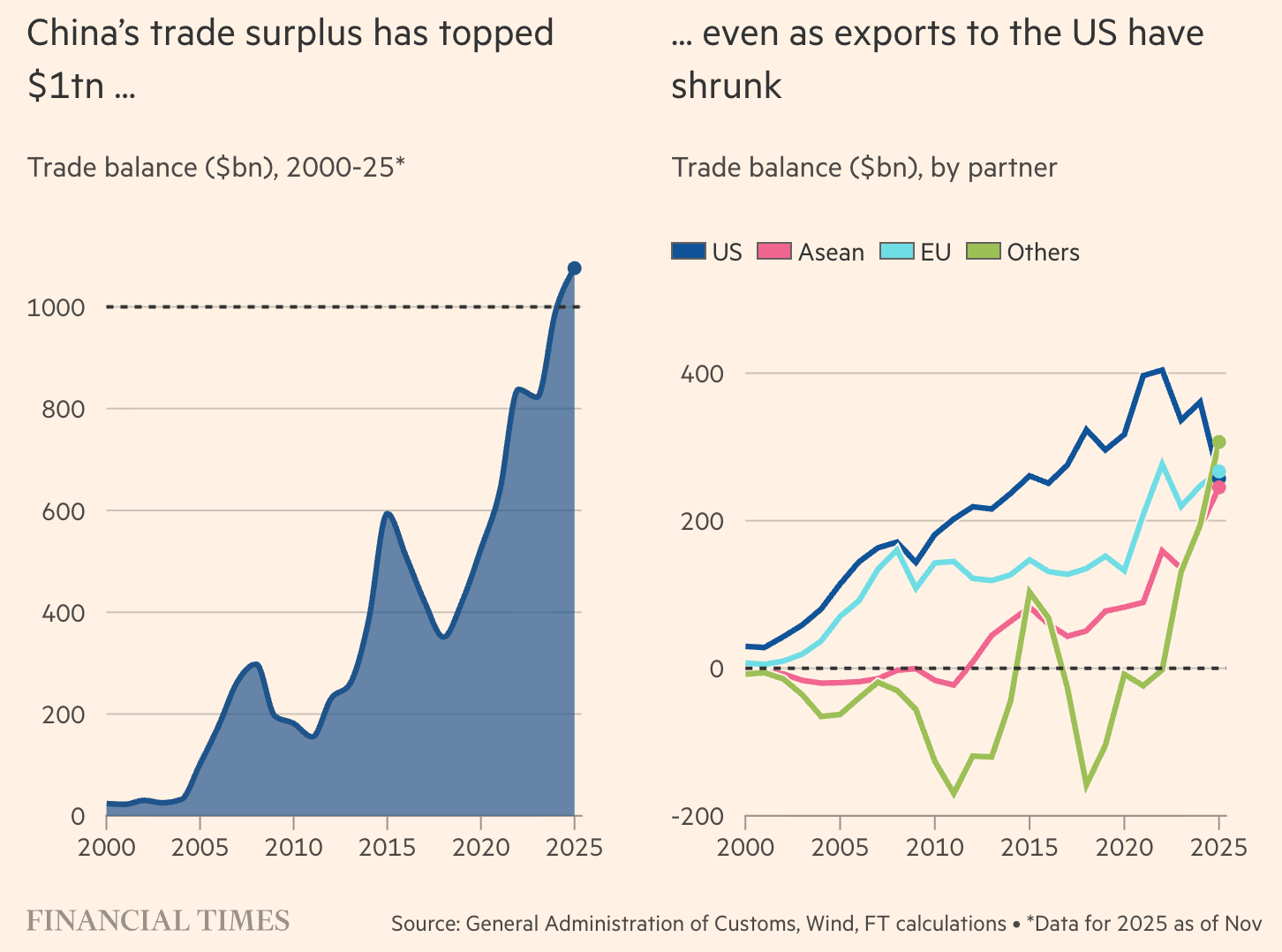

This week, China announced that so far this year, it has exported $1.08 trillion more in goods than it has imported. Amid technological revolutions, grinding poverty and aging demographics, this may still be the most important single statistic to understand about the immediate future of the world’s economy.

It's not just that Chinese leaders don’t take complaints seriously. It’s not clear that they can stop pumping all this stuff into global markets if they wanted to.

Think of it, for now, as a runaway train.

Over the last three decades, the Chinese government has built an export powerhouse intended to lift its people out of poverty. Initially, China’s exports consisted of basic materials such as steel, concrete, and coal. Today, the country sends expanding volumes of electric vehicles, solar panels, advanced industrial machinery and pharmaceuticals into markets around the world at cut-rate prices that undermine the local competition.

Some of this momentum comes from government subsidies, cheap credit and other direct support. Some of it is the result of weak domestic demand that has long been suppressed and continues to suffer in the aftermath of the housing crisis. Some of it is the result of a complex set of political and tax incentives that encourage regional officials to support top-line production with little regard to corporate profitability.

The most recent print is especially notable because it comes in the wake of the Trump administration's tariffs, which have sent direct shipments to the United States plummeting. But China’s exports to Europe, Southeast Asia and other countries have soared. Many of these are merely transhipments that will end up in America anyway. Still, many continue to flood local markets from Germany to Thailand to South Africa, fueling a rising wave of resentment toward Beijing.

To the extent that Chinese officials worry about the economic Frankenstein they have created, they have begun to focus on hyper-competition among private firms that is driving down profitability and threatens deflation. They call it “involution,” but it’s not entirely clear what they can do, short of dramatically rewiring their political and economic systems. Forcing consolidation or bankruptcies will aggravate employment problems that are already worrying. Moreover, it’s a stretch to hope they can rework a vast network of party officials who have been trained to believe that more is better.

It would, of course, help to have the United States join its allies and partners around the world to speak with a single voice about what may be the global economy's most important problem. But that doesn’t seem to be the case for President Trump, as he seeks a bilateral trade deal with President Xi.

Meanwhile, the train is gaining speed, and no one seems able to stop it.

A blind runaway train on one side and an unmoored ship yelling "America first! by way of compensation for the aimless drift on the other. Sounds like a recipe for something? What do you make of the somewhat downplayed version of the PRC in the 2025 NSS?